In a previous life, I worked for a location-based entertainment company, part

of a huge team of people developing a location for Las Vegas, Nevada. It was

COVID, a rough time for location-based anything, and things were delayed more

than usual. Coworkers paid a lot of attention to another upcoming Las Vegas

attraction, one with a vastly larger budget but still struggling to make

schedule: the MSG (Madison Square Garden) Sphere.

I will set aside jokes about it being a square sphere, but they were perhaps

one of the reasons that it underwent a pre-launch rebranding to merely the

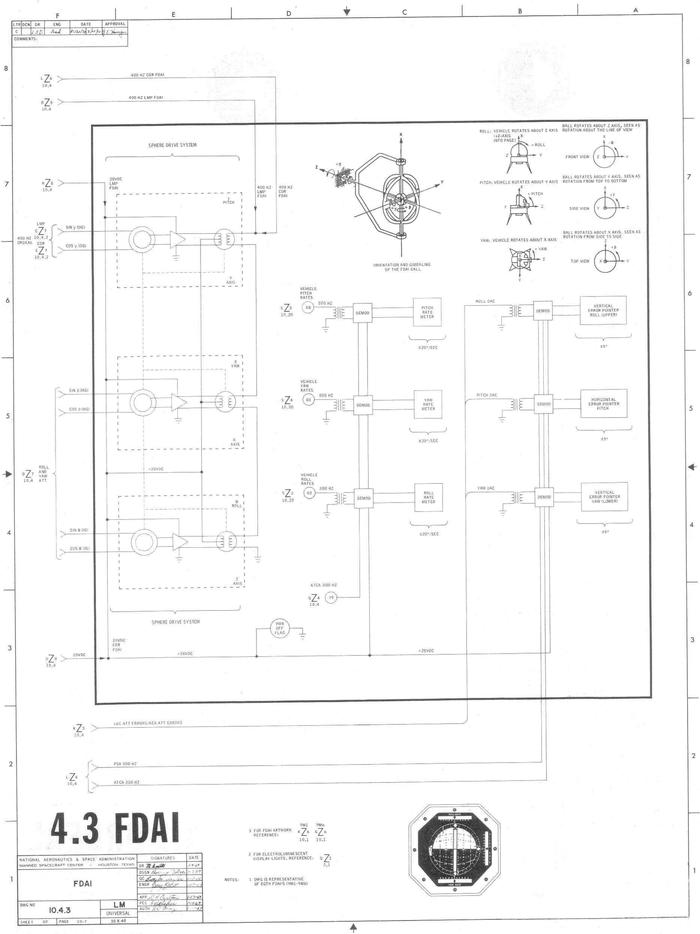

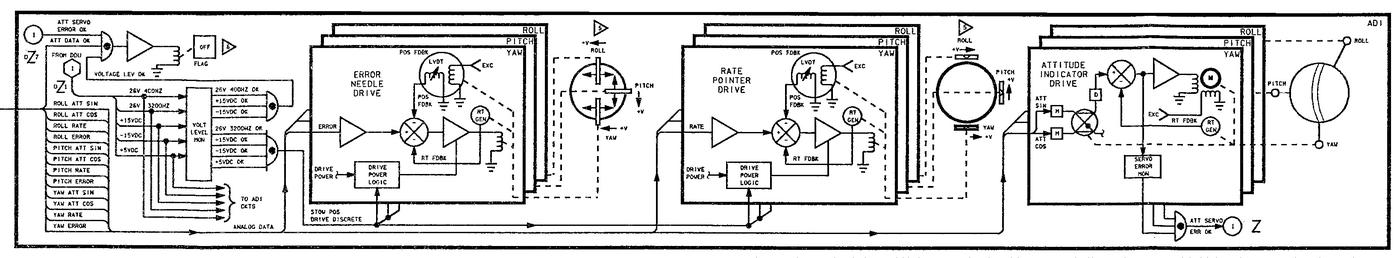

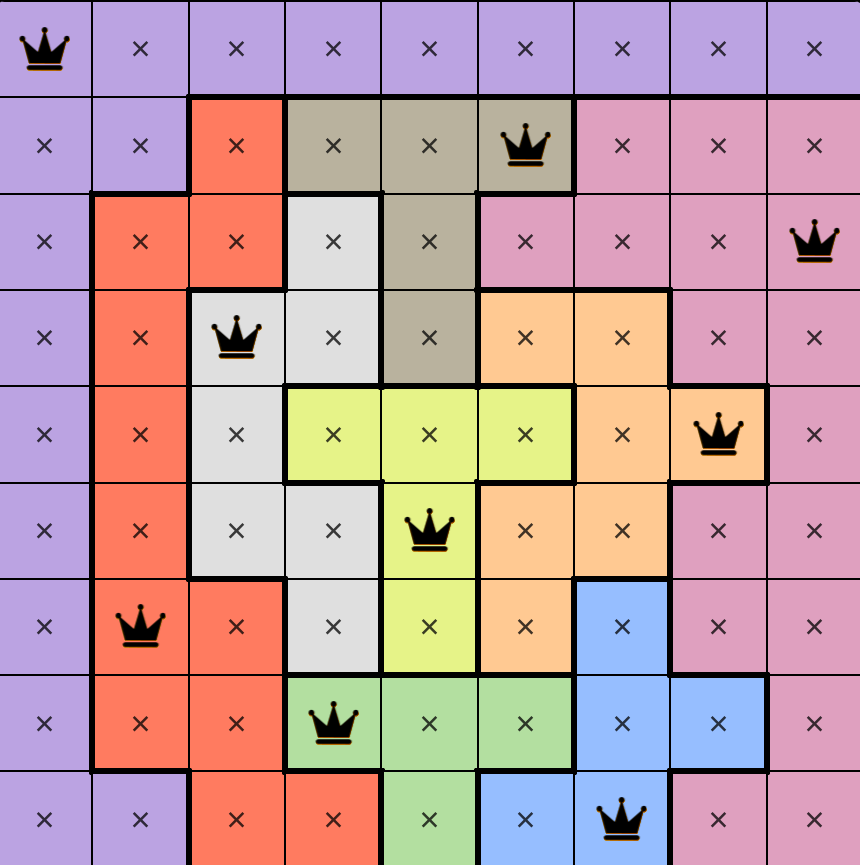

Sphere. If you are not familiar, the Sphere is a theater and venue in Las

Vegas. While it's know mostly for the video display on the outside, that's

just marketing for the inside: a digital dome theater, with seating at a

roughly 45 degree stadium layout facing a near hemisphere of video displays.

It is a "near" hemisphere because the lower section is truncated to allow a

flat floor, which serves as a stage for events but is also a practical

architectural decision to avoid completely unsalable front rows. It might seem

a little bit deceptive that an attraction called the Sphere does not quite pull

off even a hemisphere of "payload," but the same compromise has been reached by

most dome theaters. While the use of digital display technology is flashy,

especially on the exterior, the Sphere is not quite the innovation that it

presents itself as. It is just a continuation of a long tradition of dome

theaters. Only time will tell, but the financial difficulties of the Sphere

suggest that it follows the tradition faithfully: towards commercial failure.

You could make an argument that the dome theater is hundreds of years old, but

I will omit it. Things really started developing, at least in our modern

tradition of domes, with the 1923 introduction of the Zeiss planetarium

projector. Zeiss projectors and their siblings used a complex optical and

mechanical design to project accurate representations of the night sky. Many

auxiliary projectors, incorporated into the chassis and giving these projectors

famously eccentric shapes, rendered planets and other celestial bodies. Rather

than digital light modulators, the images from these projectors were formed by

purely optical means: perforated metal plates, glass plates with etched

metalized layers, and fiber optics. The large, precisely manufactured image

elements and specialized optics created breathtaking images.

While these projectors had considerable entertainment value, especially in the

mid-century when they represented some of the most sophisticated projection

technology yet developed, their greatest potential was obviously in education.

Planetarium projectors were fantastically expensive (being hand-built in

Germany with incredible component counts) [1], they were widely installed in

science museums around the world. Most of us probably remember a dogbone-shaped

Zeiss, or one of their later competitors like Spitz or Minolta, from our

youths. Unfortunately, these marvels of artistic engineering were mostly

retired as digital projection of near comparable quality became similarly

priced in the 2000s.

But we aren't talking about projectors, we're talking about theaters.

Planetarium projectors were highly specialized to rendering the night sky, and

everything about them was intrinsically spherical. For both a reasonable

viewing experience, and for the projector to produce a geometrically correct

image, the screen had to be a spherical section. Thus the planetarium itself:

in its most traditional form, rings of heavily reclined seats below a

hemispherical dome. The dome was rarely a full hemisphere, but was usually

truncated at the horizon. This was mostly a practical decision but integrated

well into the planetarium experience, given that sky viewing is usually poor

near the horizon anyway. Many planetaria painted a city skyline or forest

silhouette around the lower edge to make the transition from screen to wall

more natural. Later, theatrical lighting often replaced the silhouette,

reproducing twilight or the haze of city lights.

Unsurprisingly, the application-specific design of these theaters also limits

their potential. Despite many attempts, the collective science museum industry

has struggled to find entertainment programming for planetaria much beyond Pink

Floyd laser shows [2]. There just aren't that many things that you look up

at. Over time, planetarium shows moved in more narrative directions. Film

projection promised new flexibility---many planetaria with optical star

projectors were also equipped with film projectors, which gave show producers

exciting new options. Documentary video of space launches and animations of

physical principles became natural parts of most science museum programs, but

were a bit awkward on the traditional dome. You might project four copies of

the image just above the horizon in the four cardinal directions, for example.

It was very much a compromise.

With time, the theater adapted to the projection once again: the domes began to

tilt. By shifting the dome in one direction, and orienting the seating towards

that direction, you could create a sort of compromise point between the

traditional dome and traditional movie theater. The lower central area of the

screen was a reasonable place to show conventional film, while the full size of

the dome allowed the starfield to almost fill the audience's vision. The

experience of the tilted dome is compared to "floating in space," as opposed to

looking up at the sky.

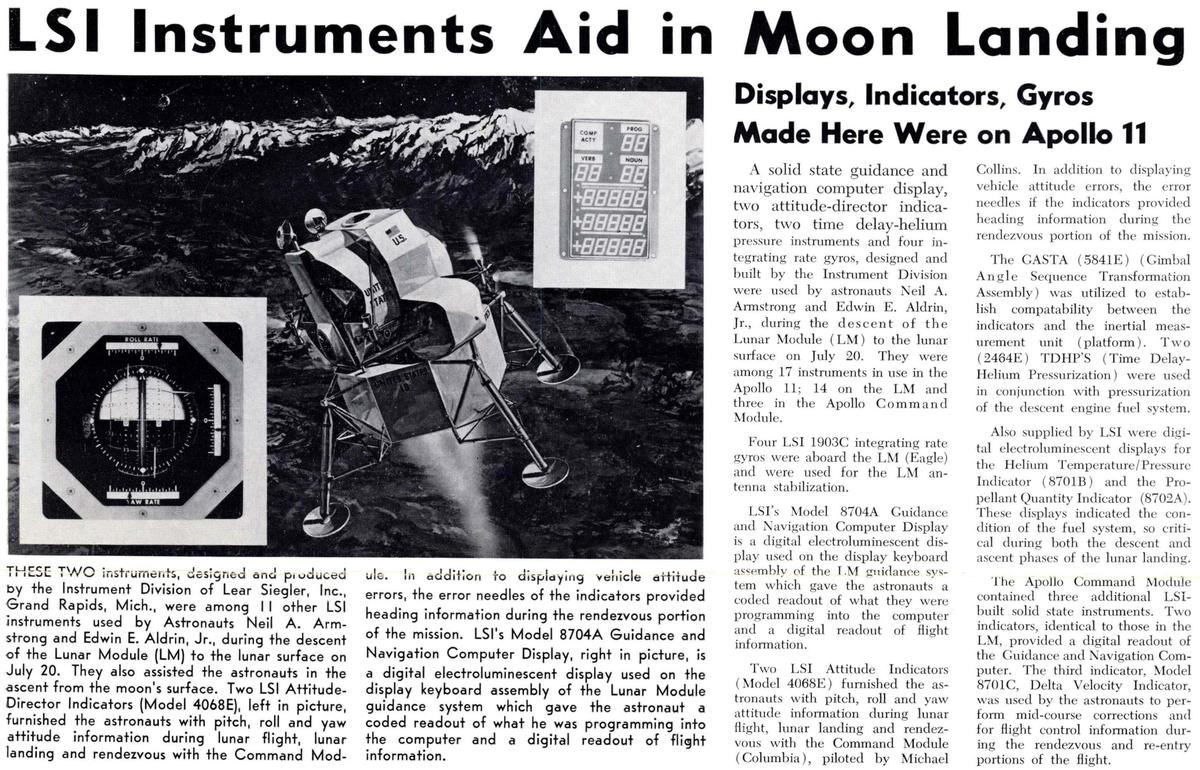

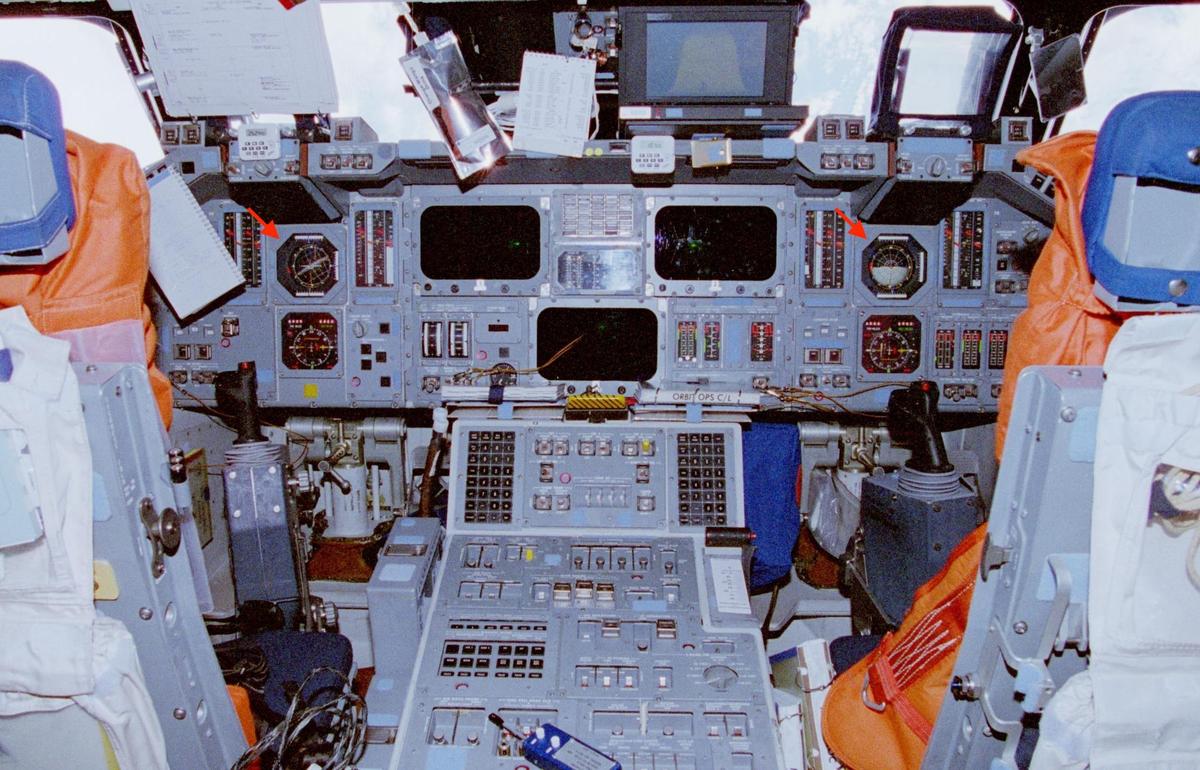

In true Cold War fashion, it was a pair of weapons engineers (one nuclear

weapons, the other missiles) who designed the first tilted planetarium. In

1973, the planetarium of what is now called the Fleet Science Center in San

Diego, California opened to the public. Its dome was tilted 25 degrees to the

horizon, with the seating installed on a similar plane and facing in one

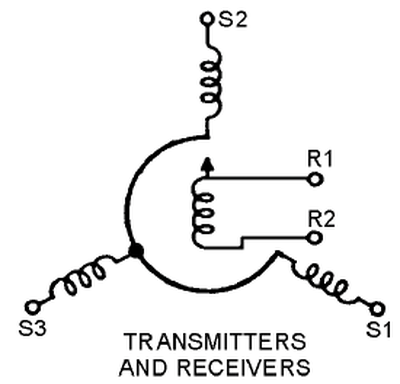

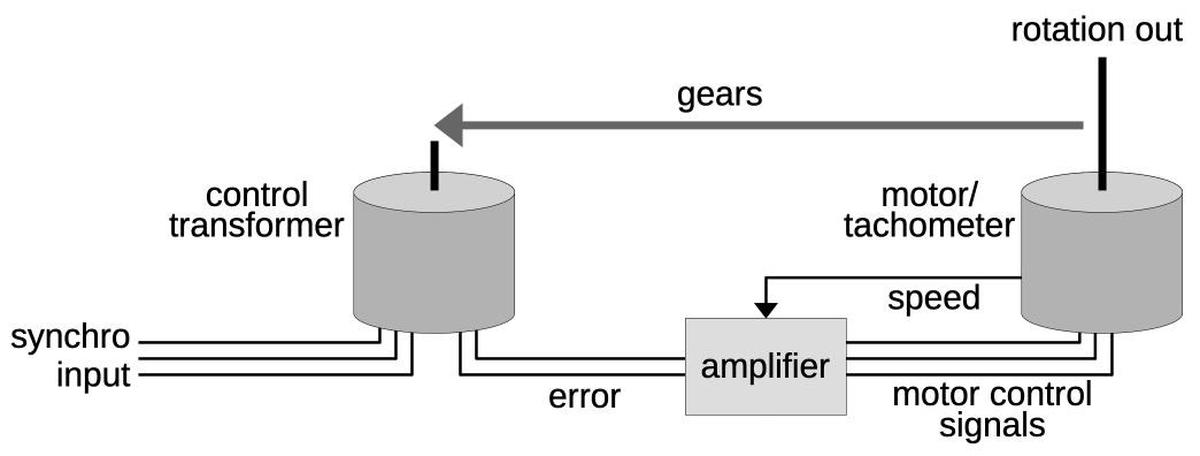

direction. It featured a novel type of planetarium projector developed by Spitz

and called the Space Transit Simulator. The STS was not the first, but still an

early mechanical projector to be controlled by a computer---a computer that

also had simultaneous control of other projectors and lighting in the theater,

what we now call a show control system.

Even better, the STS's innovative optical design allowed it to warp or bend the

starfield to simulate its appearance from locations other than earth. This was

the "transit" feature: with a joystick connected to the control computer, the

planetarium presenter could "fly" the theater through space in real time. The

STS was installed in a well in the center of the seating area, and its compact

chassis kept it low in the seating area, preserving the spherical geometry (with

the projector at the center of the sphere) without blocking the view of audience

members sitting behind it and facing forward.

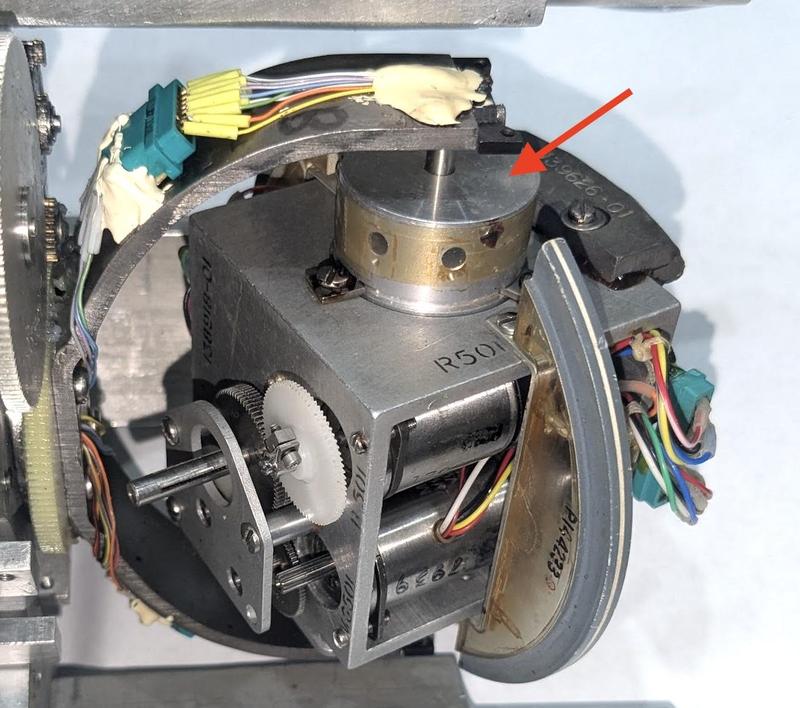

And yet my main reason for discussing the Fleet planetarium is not the the

planetarium projector at all. It is a second projector, an "auxiliary" one,

installed in a second well behind the STS. The designers of the planetarium

intended to show film as part of their presentations, but they were not content

with a small image at the center viewpoint. The planetarium commissioned a few

of the industry's leading film projection experts to design a film projection

system that could fill the entire dome, just as the planetarium projector did.

They knew that such a large dome would require an exceptionally sharp image.

Planetarium projectors, with their large lithographed slides, offered excellent

spatial resolution. They made stars appear as point sources, the same as in the

night sky. 35mm film, spread across such a large screen, would be obviously

blurred in comparison. They would need a very large film format.

Fortuitously, almost simultaneously the Multiscreen Corporation was developing

a "sideways" 70mm format. This 15-perf format used 70mm film but fed it through

the projector sideways, making each frame much larger than typical 70mm film.

In its debut, at a temporary installation in the 1970 Expo Osaka, it was dubbed

IMAX. IMAX made an obvious basis for a high-resolution projection system, and

so the then-named IMAX Corporation was added to the planetarium project. The

Fleet's film projector ultimately consisted of an IMAX film transport with a

custom-built compact, liquid-cooled lamphouse and spherical fisheye lens

system.

The large size of the projector, the complex IMAX framing system and cooling

equipment, made it difficult to conceal in the theater's projector well.

Threading film into IMAX projectors is quite complex, with several checks the

projectionist must make during a pre-show inspection. The projectionist needed

room to handle the large film, and to route it to and from the enormous reels.

The projector's position in the middle of the seating area left no room for any

of this. We can speculate that it was, perhaps, one of the designer's missile

experience that lead to the solution: the projector was serviced in a large

projection room beneath the theater's seating. Once it was prepared for each

show, it rose on near-vertical rails until just the top emerged in the theater.

Rollers guided the film as it ran from a platter, up the shaft to the

projector, and back down to another platter. Cables and hoses hung below the

projector, following it up and down like the traveling cable of an elevator.

To advertise this system, probably the greatest advance in film projection

since the IMAX format itself, the planetarium coined the term Omnimax.

Omnimax was not an easy or economical format. Ideally, footage had to be taken

in the same format, using a 70mm camera with a spherical lens system. These

cameras were exceptionally large and heavy, and the huge film format limited

cinematographers to short takes. The practical problems with Omnimax filming

were big enough that the first Omnimax films faked it, projecting to the larger

spherical format from much smaller conventional negatives. This was the case

for "Voyage to the Outer Planets" and "Garden Isle," the premier films at

the Fleet planetarium. The history of both is somewhat obscure, the latter

especially.

"Voyage to the Outer Planets" was executive-produced by Preston Fleet, a

founder of the Fleet center (which was ultimately named for his father, a WWII

aviator). We have Fleet's sense of showmanship to thank for the invention of

Omnimax: He was an accomplished business executive, particularly in the

photography industry, and an aviation enthusiast who had his hands in more than

one museum. Most tellingly, though, he had an eccentric hobby. He was a theater

organist. I can't help but think that his passion for the theater organ, an

instrument almost defined by the combination of many gizmos under

electromechanical control, inspired "Voyage." The film, often called a

"multimedia experience," used multiple projectors throughout the planetarium to

depict a far-future journey of exploration. The Omnimax film depicted travel

through space, with slide projectors filling in artist's renderings of the many

wonders of space.

The ten-minute Omnimax film was produced by Graphic Films Corporation, a brand

that would become closely associated with Omnimax in the following decades.

Graphic was founded in the midst of the Second World War by Lester Novros, a

former Disney animator who found a niche creating training films for the

military. Novros's fascination with motion and expertise in presenting

complicated 3D scenes drew him to aerospace, and after the war he found much of

his business in the newly formed Air Force and NASA. He was also an enthusiast

of niche film formats, and Omnimax was not his first dome.

For the 1964 New York World's Fair, Novros and Graphic Films had produced "To

the Moon and Beyond," a speculative science film with thematic similarities to

"Voyage" and more than just a little mechanical similarity. It was presented in

Cinerama 360, a semi-spherical, dome-theater 70mm format presented in a special

theater called the Moon Dome. "To the Moon and Beyond" was influential in many

ways, leading to Graphic Films' involvement in "2001: A Space Odyssey" and its

enduring expertise in domes.

The Fleet planetarium would not remain the only Omnimax for long. In 1975, the

city of Spokane, Washington struggled to find a new application for the

pavilion built for Expo '74 [3]. A top contender: an Omnimax theater, in some

ways a replacement for the temporary IMAX theater that had been constructed for

the actual Expo. Alas, this project was not to be, but others came along: in

1978, the Detroit Science Center opened the second Omnimax theater ("the

machine itself looks like and is the size of a front loader," the Detroit Free

Press wrote). The Science Museum of Minnesota, in St. Paul, followed shortly

after.

Omnimax hit prime time the next year, with the 1979 announcement of an Omnimax

theater at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada. Unlike the previous

installations, this 380-seat theater was purely commercial. It opened with the

1976 IMAX film "To Fly!," which had been optically modified to fit the Omnimax

format. This choice of first film is illuminating. "To Fly!" is a 27 minute

documentary on the history of aviation in the United States, originally

produced for the IMAX theater at the National Air and Space Museum [4]. It doesn't

exactly seem like casino fare.

The IMAX format, the flat-screen one, was born of world's fairs. It premiered

at an Expo, reappeared a couple of years later at another one, and for the

first years of the format most of the IMAX theaters built were associated with

either a major festival or an educational institution. This noncommercial

history is a bit hard to square with the modern IMAX brand, closely associated

with major theater chains and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Well, IMAX took off, and in many ways it sold out. Over the decades since the

1970 Expo, IMAX has met widespread success with commercial films and theater

owners. Simultaneously, the definition or criteria for IMAX theaters have

relaxed, with smaller screens made permissible until, ultimately, the

transition to digital projection eliminated the 70mm film and more or less

reduce IMAX to just another ticket surcharge brand. It competes directly with

Cinemark xD, for example. To the theater enthusiast, this is a pretty sad turn

of events, a Westinghouse-esque zombification of a brand that once heralded the

field's most impressive technical achievements.

The same never happened to Omnimax. The Caesar's Omnimax theater was an odd

exception; the vast majority of Omnimax theaters were built by science museums

and the vast majority of Omnimax films were science documentaries. Quite a few

of those films had been specifically commissioned by science museums, often on

the occasion of their Omnimax theater opening. The Omnimax community was fairly

tight, and so the same names recur.

The Graphic Films Corporation, which had been around since the beginning,

remained so closely tied to the IMAX brand that they practically shared

identities. Most Omnimax theaters, and some IMAX theaters, used to open with a

vanity card often known as "the wormhole." It might be hard to describe beyond

"if you know you know," it certainly made an impression on everyone I know that

grew up near a theater that used it. There are some

videos, although unfortunately

none of them are very good.

I have spent more hours of my life than I am proud to admit trying to untangle

the history of this clip. Over time, it has appeared in many theaters with many

different logos at the end, and several variations of the audio track. This is

in part informed speculation, but here is what I believe to be true: the

"wormhole" was originally created by Graphic Films for the Fleet planetarium

specifically, and ran before "Voyage to the Outer Planets" and its

double-feature companion "Garden Isle," both of which Graphic Films had worked

on. This original version ended with the name Graphic Films, accompanied by an

odd sketchy drawing that was also used as an early logo of the IMAX

Corporation. Later, the same animation was re-edited to end with an IMAX logo.

This version ran in both Omnimax and conventional IMAX theaters, probably as a

result of the extensive "cross-pollination" of films between the two formats.

Many Omnimax films through the life of the format had actually been filmed for

IMAX, with conventional lenses, and then optically modified to fit the Omnimax

dome after the fact. You could usually tell: the reprojection process created

an unusual warp in the image, and more tellingly, these pseudo-Omnimax films

almost always centered the action at the middle of the IMAX frame, which was

too high to be quite comfortable in an Omnimax theater (where the "frame

center" was well above the "front center" point of the theater). Graphic Films

had been involved in a lot of these as well, perhaps explaining the animation

reuse, but it's just as likely that they had sold it outright to the IMAX

corporation which used it as they pleased.

For some reason, this version also received new audio that is mostly the same

but slightly different. I don't have a definitive explanation, but I think

there may have been an audio format change between the very early Omnimax

theaters and later IMAX/Omnimax systems, which might have required remastering.

Later, as Omnimax domes proliferated at science museums, the IMAX Corporation

(which very actively promoted Omnimax to education) gave many of these theaters

custom versions of the vanity card that ended with the science museum's own

logo. I have personally seen two of these, so I feel pretty confident that they

exist and weren't all that rare (basically 2 out of 2 Omnimax theaters I've

visited used one), but I cannot find any preserved copies.

Another recurring name in the world of IMAX and Omnimax is MacGillivray Freeman

Films. MacGillivray and Freeman were a pair of teenage friends from Laguna

Beach who dropped out of school in the '60s to make skateboard and surf films.

This is, of course, a rather cliché start for documentary filmmakers but we

must allow that it was the '60s and they were pretty much the ones creating the

cliché. Their early films are hard to find in anything better than VHS rip

quality, but worth watching: Wikipedia notes their significance in pioneering

"action cameras," mounting 16mm cinema cameras to skateboards and surfboards,

but I would say that their cinematography was innovative in more ways than just

one. The 1970 "Catch the Joy," about sandrails, has some incredible shots that

I struggle to explain. There's at least one where they definitely cut the shot

just a couple of frames before a drifting sandrail flung their camera all the

way down the dune.

For some reason, I would speculate due to their reputation for exciting

cinematography, the National Air and Space Museum chose MacGillivray and

Freeman for "To Fly!". While not the first science museum IMAX documentary by

any means (that was, presumably, "Voyage to the Outer Planets" given the

different subject matter of the various Expo films), "To Fly!" might be called

the first modern one. It set the pattern that decades of science museum films

followed: a film initially written by science educators, punched up by

producers, and filmed with the very best technology of the time. Fearing that

the film's history content would be dry, they pivoted more towards

entertainment, adding jokes and action sequences. "To Fly!" was a hit, running

in just about every science museum with an IMAX theater, including Omnimax.

Sadly, Jim Freeman died in a helicopter crash shortly after production.

Nonetheless, MacGillivray Freeman Films went on. Over the following decades,

few IMAX science documentaries were made that didn't involve them somehow.

Besides the films they produced, the company consulted on action sequences

in most of the format's popular features.

I had hoped to present here a thorough history of the films that were actually

produced in the Omnimax format. Unfortunately, this has proven very difficult:

the fact that most of them were distributed only to science museums means that

they are very spottily remembered, and besides, so many of the films that ran

in Omnimax theaters were converted from IMAX presentations that it's hard to

tell the two apart. I'm disappointed that this part of cinema history isn't

better recorded, and I'll continue to put time into the effort. Science museum

documentaries don't get a lot of attention, but many of the have involved

formidable technical efforts.

Consider, for example, the cameras: befitting the large film, IMAX cameras

themselves are very large. When filming "To Fly!", MacGillivray and Freeman

complained that the technically very basic 80 pound cameras required a lot of

maintenance, were complex to operate, and wouldn't fit into the "action cam"

mounting positions they were used to. The cameras were so expensive, and so

rare, that they had to be far more conservative than their usual approach out

of fear of damaging a camera they would not be able to replace. It turns out

that they had it easy. Later IMAX science documentaries would be filmed in

space ("The Dream is Alive" among others) and deep underwater ("Deep Sea 3D"

among others). These IMAX cameras, modified for simpler operation and housed

for such difficult environments, weighed over 1,000 pounds. Astronauts had to

be trained to operate the cameras; mission specialists on Hubble service

missions had wrangling a 70-pound handheld IMAX camera around the cabin and

developing its film in a darkroom bag among their duties. There was a lot of

film to handle: as a rule of thumb, one mile of IMAX film is good for eight

and a half minutes.

I grew up in Portland, Oregon, and so we will make things a bit more

approachable by focusing on one example: The Omnimax theater of the Oregon

Museum of Science and Industry, which opened as part of the museum's new

waterfront location in 1992. This 330-seat boasted a 10,000 sq ft dome and 15

kW of sound. The premier feature was "Ring of Fire," a volcano documentary

originally commissioned by the Fleet, the Fort Worth Museum of Science and

Industry, and the Science Museum of Minnesota. By the 1990s, the later era of

Omnimax, the dome format was all but abandoned as a commercial concept. There

were, an announcement article notes, around 90 total IMAX theaters (including

Omnimax) and 80 Omnimax films (including those converted from IMAX) in '92.

Considering the heavy bias towards science museums among these theaters, it

was very common for the films to be funded by consortia of those museums.

Considering the high cost of filming in IMAX, a lot of the documentaries had a

sort of "mashup" feel. They would combine footage taken in different times and

places, often originally for other projects, into a new narrative. "Ring of

Fire" was no exception, consisting of a series of sections that were sometimes

more loosely connected to the theme. The 1982 Loma Prieta earthquake was a

focus, and the eruption of Mt. St. Helens, and lava flows in Hawaii. Perhaps

one of the reasons it's hard to catalog IMAX films is this mashup quality, many

of the titles carried at science museums were something along the lines of

"another ocean one." I don't mean this as a criticism, many of the IMAX

documentaries were excellent, but they were necessarily composed from

painstakingly gathered fragments and had to cover wide topics.

Given that I have an announcement feature piece in front of me, let's also use

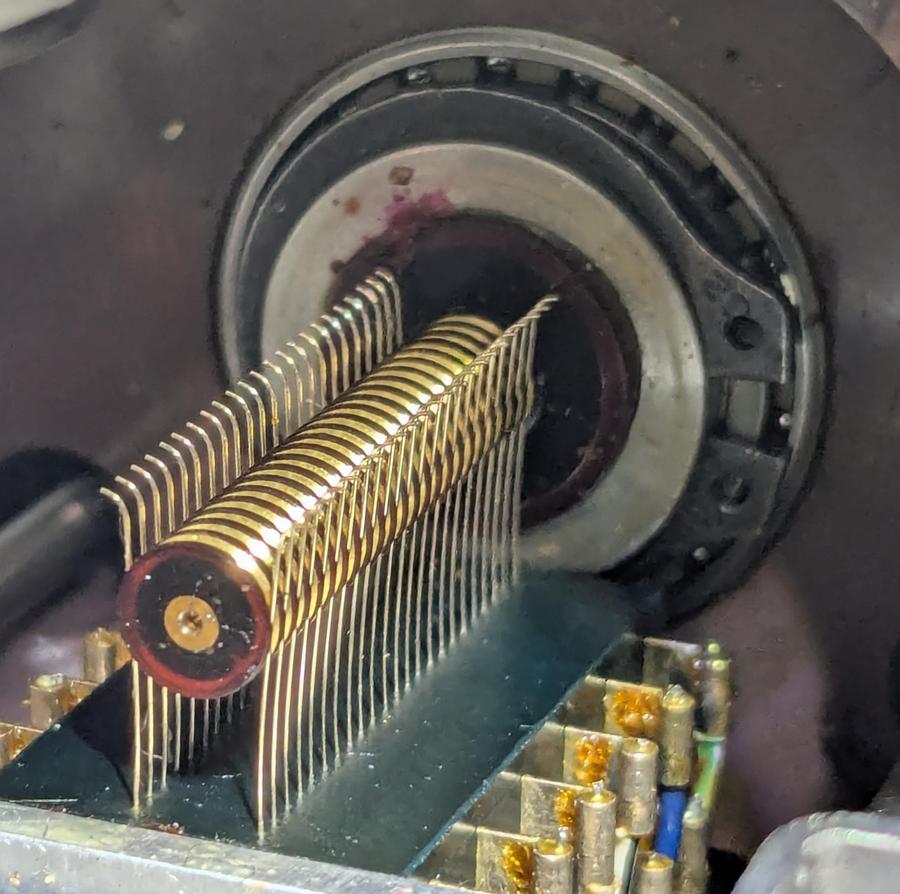

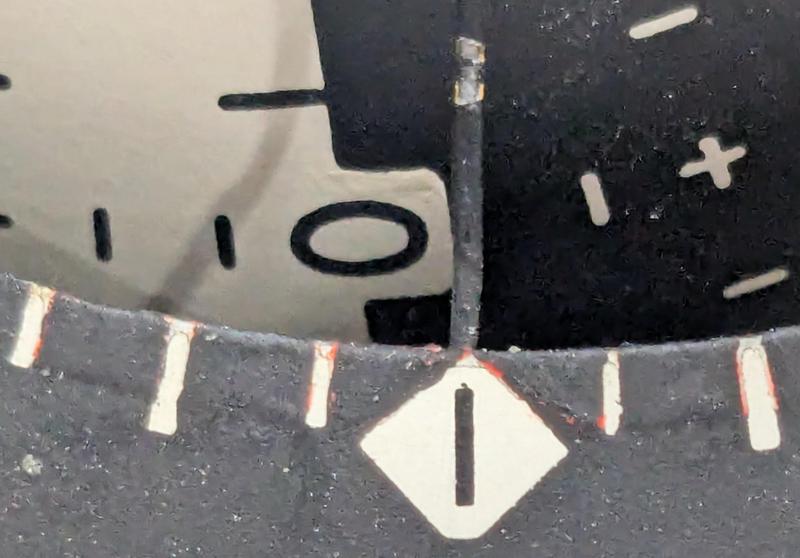

the example of OMSI to discuss the technical aspects. OMSI's projector cost

about $2 million and weighted about two tons. To avoid dust damaging the

expensive prints, the "projection room" under the seating was a

positive-pressure cleanroom. This was especially important since the paucity of

Omnimax content meant that many films ran regularly for years. The 15 kW

water-cooled lamp required replacement at 800 to 1,000 hours, but

unfortunately, the price is not noted.

By the 1990s, Omnimax had become a rare enough system that the projection

technology was a major part of the appeal. OMSI's installation, like most later

Omnimax theaters, had the audience queue below the seating, separated from the

projection room by a glass wall. The high cost of these theaters meant that

they operated on high turnovers, so patrons would wait in line to enter

immediately after the previous showing had exited. While they waited, they

could watch the projectionist prepare the next show while a museum docent

explained the equipment.

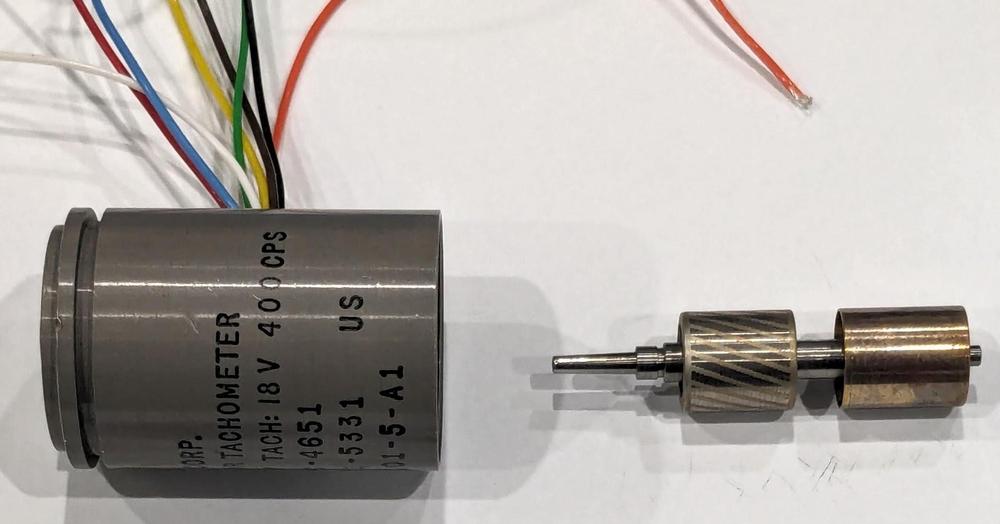

I have written before about multi-channel audio

formats, and

Omnimax gives us some more to consider. The conventional audio format for much

of Omnimax's life was six-channel: left rear, left screen, center screen, right

screen, right rear, and top. Each channel had an independent bass cabinet (in

one theater, a "caravan-sized" enclosure with eight JBL 2245H 46cm woofers),

and a crossover network fed the lowest end of all six channels to a "sub-bass"

array at screen bottom. The original Fleet installation also had sub-bass

speakers located beneath the audience seating, although that doesn't seem to

have become common.

IMAX titles of the '70s and '80s delivered audio on eight-track magnetic tape,

with the additional tracks used for synchronization to the film. By the '90s,

IMAX had switched to distributing digital audio on three CDs (one for each two

channels). OMSI's theater was equipped for both, and the announcement amusingly

notes the availability of cassette decks. A semi-custom audio processor made

for IMAX, the Sonics TAC-86, managed synchronization with film playback and

applied equalization curves individually calibrated to the theater.

IMAX domes used perforated aluminum screens (also the norm in later

planetaria), so the speakers were placed behind the screen in the scaffold-like

superstructure that supported it. When I was young, OMSI used to start

presentations with a demo program that explained the large size of IMAX film

before illuminating work lights behind the screen to make the speakers visible.

Much of this was the work of the surprisingly sophisticated show control system

employed by Omnimax theaters, a descendent of the PDP-15 originally installed

in the Fleet.

Despite Omnimax's almost complete consignment to science museums, there were

some efforts at bringing commercial films. Titles like Disney's "Fantasia" and

"Star Wars: Episode III" were distributed to Omnimax theaters via optical

reprojection, sometimes even from 35mm originals. Unfortunately, the quality of

these adaptations was rarely satisfactory, and the short runtimes (and

marketing and exclusivity deals) typical of major commercial releases did not

always work well with science museum schedules. Still, the cost of converting

an existing film to dome format is pretty low, so the practice continues today.

"Star Wars: The Force Awakens," for example, ran on at least one science museum

dome. This trickle of blockbusters was not enough to make commercial Omnimax

theaters viable.

Caesars Palace closed, and then demolished, their Omnimax theater in 2000. The

turn of the 21st century was very much the beginning of the end for the dome

theater. IMAX was moving away from their film system and towards digital

projection, but digital projection systems suitable for large domes were still

a nascent technology and extremely expensive. The end of aggressive support

from IMAX meant that filming costs became impractical for documentaries, so

while some significant IMAX science museum films were made in the 2000s, the

volume definitely began to lull and the overall industry moved away from IMAX

in general and Omnimax especially.

It's surprising how unforeseen this was, at least to some. A ten-screen

commercial theater in Duluth opened an Omnimax theater in 1996! Perhaps due to

the sunk cost, it ran until 2010, not a bad closing date for an Omnimax

theater. Science museums, with their relatively tight budgets and less

competitive nature, did tend to hold over existing Omnimax installations well

past their prime. Unfortunately, many didn't: OMSI, for example, closed its

Omnimax theater in 2013 for replacement with a conventional digital theater

that has a large screen but is not IMAX branded.

Fortunately, some operators hung onto their increasingly costly Omnimax domes

long enough for modernization to become practical. The IMAX Corporation

abandoned the Omnimax name as more of the theaters closed, but continued to

support "IMAX Dome" with the introduction of a digital laser projector with

spherical optics. There are only ten examples of this system. Others, including

Omnimax's flagship at the Fleet Science Center, have been replaced by custom

dome projection systems built by competitors like Sony.

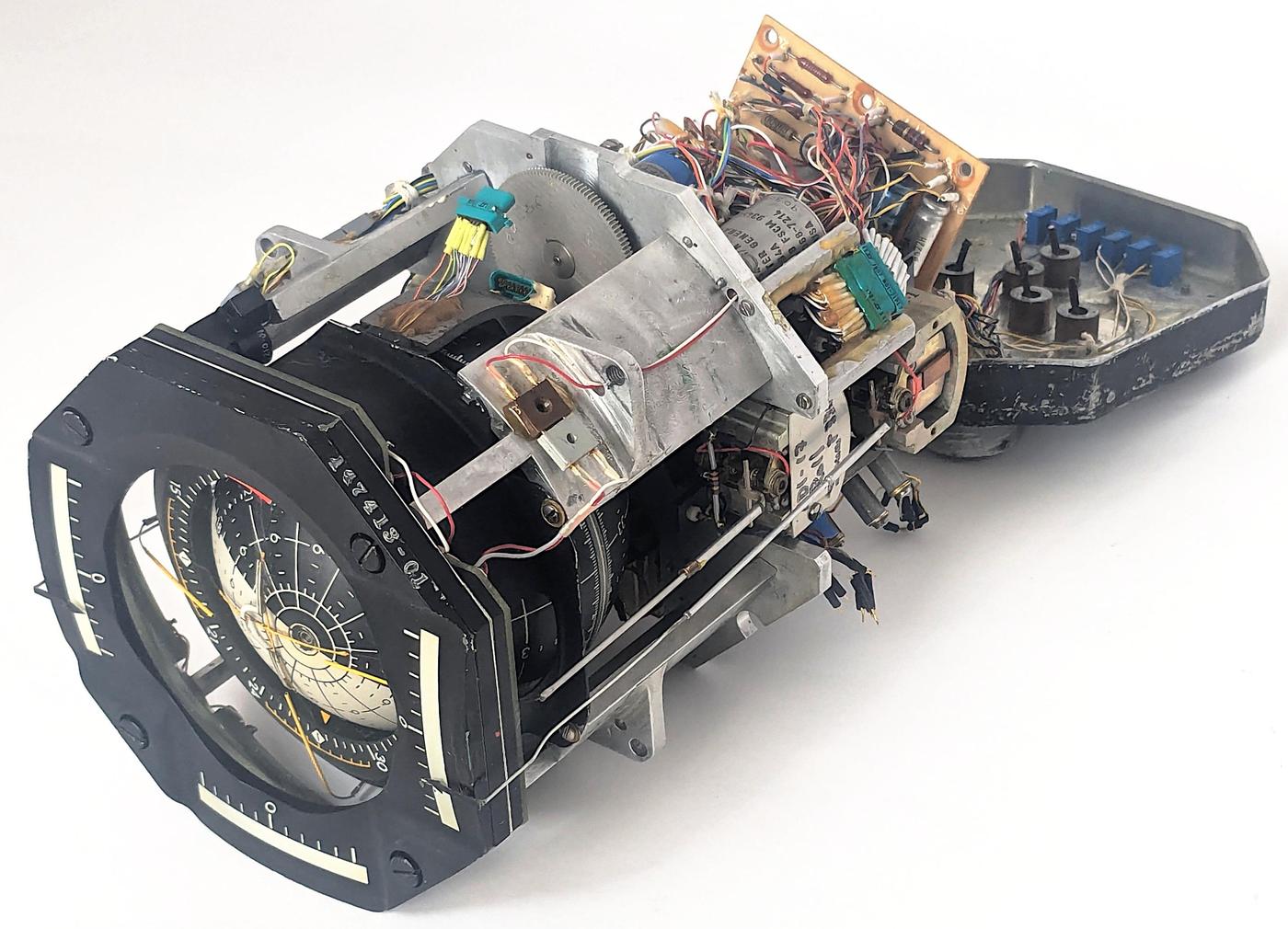

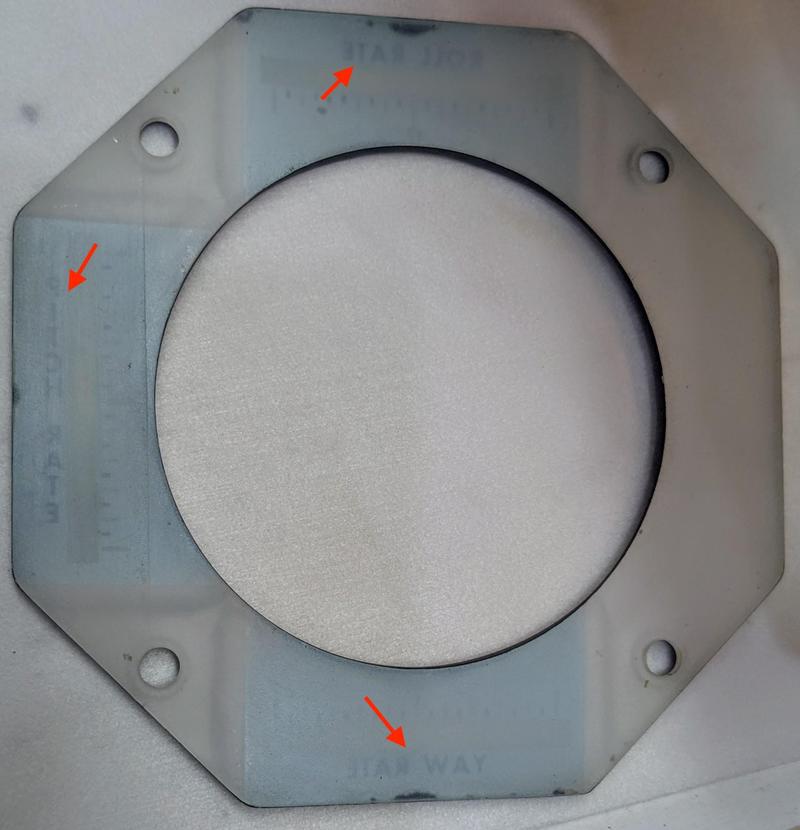

Few Omnimax projectors remain. The Fleet, to their credit, installed the modern

laser projectors in front of the projector well so that the original film

projector could remain in place. It's still functional and used for reprisals

of Omnimax-era documentaries. IMAX projectors in general are a dying breed, a

number of them have been preserved but their complex, specialized design and

the end of vendor support means that it may become infeasible to keep them

operating.

We are, of course, well into the digital era. While far from inexpensive,

digital projection systems are now able to match the quality of Omnimax

projection. The newest dome theaters, like the Sphere, dispense with

projection entirely. Instead, they use LED display panels capable of far

brighter and more vivid images than projection, and with none of the complexity

of water-cooled arc lamps.

Still, something has been lost. There was once a parallel theater industry, a

world with none of the glamor of Hollywood but for whom James Cameron hauled a

camera to the depths of the ocean and Leonardo DiCaprio narrated repairs to the

Hubble. In a good few dozen science museums, two-ton behemoths rose from

beneath the seats, the zenith of film projection technology. After decades of

documentaries, I think people forgot how remarkable these theaters were.

Science museums stopped promoting them as aggressively, and much of the

showmanship faded away. Sometime in the 2000s, OMSI stopped running the

pre-show demonstration, instead starting the film directly. They stopped

explaining the projectionist's work in preparing the show, and as they shifted

their schedule towards direct repetition of one feature, there was less for the

projectionist to do anyway. It became just another museum theater, so it's no

wonder that they replaced it with just another museum theater: a generic

big-screen setup with the exceptionally dull name of "Empirical Theater."

From time to time, there have been whispers of a resurgence of 70mm film.

Oppenheimer, for example, was distributed to a small number of theaters in this

giant of film formats: 53 reels, 11 miles, 600 pounds of film. Even

conventional IMAX is too costly for the modern theater industry, though.

Omnimax has fallen completely by the wayside, with the few remaining dome

operators doomed to recycling the same films with a sprinkling of newer

reformatted features. It is hard to imagine a collective of science museums

sending another film camera to space.

Omnimax poses a preservation challenge in more ways than one. Besides the lack

of documentation on Omnimax theaters and films, there are precious few

photographs of Omnimax theaters and even fewer videos of their presentations.

Of course, the historian suffers where Madison Square Garden hopes to succeed:

the dome theater is perhaps the ultimate in location-based entertainment.

Photos and videos, represented on a flat screen, cannot reproduce the

experience of the Omnimax theater. The 180 horizontal degrees of screen, the

sound that was always a little too loud, in no small part to mask the sound of

the projector that made its own racket in the middle of the seating. You had to

be there.

IMAGES: Omnimax projection room at OMSI, Flickr user truk. Omnimax dome with

work lights on at MSI Chicago, Wikimedia Commons user GualdimG. Omnimax

projector at St. Louis Science Center, Flickr user pasa47.

[1] I don't have extensive information on pricing, but I know that in the 1960s

an "economy" Spitz came in over $30,000 (~10x that much today).

[2] Pink Floyd's landmark album Dark Side of The Moon debuted in a release

event held at the London Planetarium. This connection between Pink Floyd and

planetaria, apparently much disliked by the band itself, has persisted to the

present day. Several generations of Pink Floyd laser shows have been licensed

by science museums around the world, and must represent by far the largest

success of fixed-installation laser projection.

[3] Are you starting to detect a theme with these Expos? the World's Fairs,

including in their various forms as Expos, were long one of the main markets

for niche film formats. Any given weird projection format you run into, there's

a decent chance that it was originally developed for some short film for an

Expo. Keep in mind that it's the nature of niche projection formats that they

cannot easily be shown in conventional theaters, so they end up coupled to

these crowd events where a custom venue can be built.

[4] The Smithsonian Institution started looking for an exciting new theater in

1970. As an example of the various niche film formats at the time, the

Smithsonian considered a dome (presumably Omnimax), Cinerama (a three-projector

ultrawide system), and Circle-Vision 360 (known mostly for the few surviving

Expo films at Disney World's EPCOT) before settling on IMAX. The Smithsonian

theater, first planned for the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History before

being integrated into the new National Air and Space Museum, was tremendously

influential on the broader world of science museum films. That is perhaps an

understatement, it is sometimes credited with popularizing IMAX in general, and

the newspaper coverage the new theater received throughout North America lends

credence to the idea. It is interesting, then, to imagine how different our

world would be if they had chosen Circle-Vision. "Captain America: Brave New

World" in Cinemark 360.