RuBee

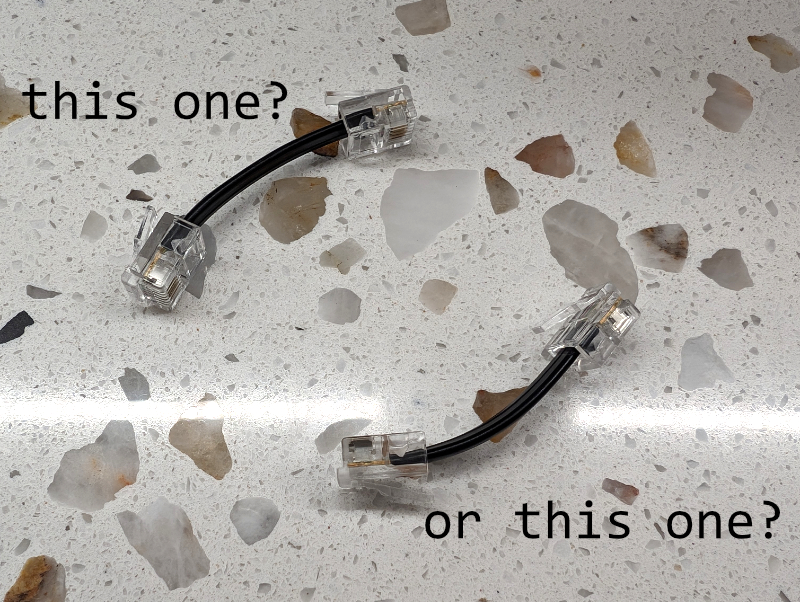

I have at least a few readers for which the sound of a man's voice saying "government cell phone detected" will elicit a palpable reaction. In Department of Energy facilities across the country, incidences of employees accidentally carrying phones into secure areas are reduced through a sort of automated nagging. A device at the door monitors for the presence of a tag; when the tag is detected it plays an audio clip. Because this is the government, the device in question is highly specialized, fantastically expensive, and says "government cell phone" even though most of the phones in question are personal devices. Look, they already did the recording, they're not changing it now!

One of the things that I love is weird little wireless networks. Long ago I wrote about ANT+, for example, a failed personal area network standard designed mostly around fitness applications. There's tons of these, and they have a lot of similarities---so it's fun to think about the protocols that went down a completely different path. It's even better, of course, if the protocol is obscure outside of an important niche. And a terrible website, too? What more could I ask for.

The DoE's cell-phone nagging boxes, and an array of related but more critical applications, rely on an unusual personal area networking protocol called RuBee.

RuBee is a product of Visible Assets Inc., or VAI, founded in 2004 1 by John K. Stevens. Stevens seems a somewhat improbable founder, with a background in biophysics and eye health, but he's a repeat entrepreneur. He's particularly fond of companies called Visible: he founded Visible Assets after his successful tenure as CEO of Visible Genetics. Visible Genetics was an early innovator in DNA sequencing, and still provides a specialty laboratory service that sequences samples of HIV in order to detect vulnerabilities to antiretroviral medications.

Clinical trials in the early 2000s exposed Visible Genetics to one of the more frustrating parts of health care logistics: refrigeration. Samples being shipped to the lab and reagents shipped out to clinics were both temperature sensitive. Providers had to verify that these materials had stayed adequately cold throughout shipping and handling, otherwise laboratory results could be invalid or incorrect. Stevens became interested in technical solutions to these problems; he wanted some way to verify that samples were at acceptable temperatures both in storage and in transit.

Moreover, Stevens imagined that these sensors would be in continuous communication. There's a lot of overlap between this application and personal area networks (PANs), protocols like Bluetooth that provide low-power communications over short ranges. There is also clear overlap with RFID; you can buy RFID temperature sensors. VAI, though, coined the term visibility network to describe RuBee. That's visibility as in asset visibility: somewhat different from Bluetooth or RFID, RuBee as a protocol is explicitly designed for situations where you need to "keep tabs" on a number of different objects. Despite the overlap with other types of wireless communications, the set of requirements on a visibility network have lead RuBee down a very different technical path.

Visibility networks have to be highly reliable. When you are trying to keep track of an asset, a failure to communicate with it represents a fundamental failure of the system. For visibility networks, the ability to actually convey a payload is secondary: the main function is just reliably detecting that endpoints exist. Visibility networks have this in common with RFID, and indeed, despite its similarities to technologies like BLE RuBee is positioned mostly as a competitor to technologies like UHF RFID.

There are several differences between RuBee and RFID; for example, RuBee uses active (battery-powered) tags and the tags are generally powered by a complete 4-bit microcontroller. That doesn't necessarily sound like an advantage, though. While RuBee tags advertise a battery life of "5-25 years", the need for a battery seems mostly like a liability. The real feature is what active tags enable: RuBee operates in the low frequency (LF) band, typically at 131 kHz.

At that low frequency, the wavelength is very long, about 2.5 km. With such a long wavelength, RuBee communications all happen at much less than one wavelength in range. RF engineers refer to this as near-field operation, and it has some properties that are intriguingly different from more typical far-field RF communications. In the near-field, the magnetic field created by the antenna is more significant than the electrical field. RuBee devices are intentionally designed to emit very little electrical RF signal. Communications within a RuBee network are achieved through magnetic, not electrical fields. That's the core of RuBee's magic.

The idea of magnetic coupling is not unique to RuBee. Speaking of the near-field, there's an obvious comparison to NFC which works much the same way. The main difference, besides the very different logical protocols, is that NFC operates at 13.56 MHz. At this higher frequency, the wavelength is only around 20 meters. The requirement that near-field devices be much closer than a full wavelength leads naturally to NFC's very short range, typically specified as 4 cm.

At LF frequencies, RuBee can achieve magnetic coupling at ranges up to about 30 meters. That's a range comparable to, and often much better than, RFID inventory tracking technologies. Improved range isn't RuBee's only benefit over RFID. The properties of magnetic fields also make it a more robust protocol. RuBee promises significantly less vulnerability to shielding by metal or water than RFID.

There are two key scenarios where this comes up: the first is equipment stored in metal containers or on metal shelves, or equipment that is itself metallic. In that scenario, it's difficult to find a location for an RFID tag that won't suffer from shielding by the container. The case of water might seem less important, but keep in mind that people are made mostly of water. RFID reading is often unreliable for objects carried on a person, which are likely to be shielded from the reader by the water content of the body.

These problems are not just theoretical. WalMart is a major adopter of RFID inventory technology, and in early rollouts struggled with low successful read rates. Metal, moisture (including damp cardboard boxes), antenna orientation, and multipath/interference effects could cause read failure rates as high as 33% when scanning a pallet of goods. Low read rates are mostly addressed by using RFID "portals" with multiple antennas. Eight antennas used as an array greatly increase read rate, but at a cost of over ten thousand dollars per portal system. Even so, WalMart seems to now target a success rate of only 95% during bulk scanning.

95% might sound pretty good, but there are a lot of visibility applications where a failure rate of even a couple percent is unacceptable. These mostly go by the euphemism "high value goods," which depending on your career trajectory you may have encountered in corporate expense and property policies. High-value goods tend to be items that are both attractive to theft and where theft has particularly severe consequences. Classically, firearms and explosives. Throw in classified material for good measure.

I wonder if Stevens was surprised by RuBee's market trajectory. He came out of the healthcare industry and, it seems, originally developed RuBee for cold chain visibility... but, at least in retrospect, it's quite obvious that its most compelling application is in the armory.

Because RuBee tags are small and largely immune to shielding by metals, you can embed them directly in the frames of firearms, or as an aftermarket modification you can mill out some space under the grip. RuBee tags in weapons will read reliably when they are stored in metal cases or on metal shelving, as is often the case. They will even read reliably when a weapon is carried holstered, close to a person's body.

Since RuBee tags incorporate an active microcontroller, there are even more possibilities. Temperature logging is one thing, but firearm-embedded RuBee tags can incorporate an accelerometer (NIST-traceable, VAI likes to emphasize) and actually count the rounds fired.

Sidebar time: there is a long history of political hazard around "smart guns." The term "smart gun" is mostly used more specifically for firearms that identify their user, for example by fingerprint authentication or detection of an RFID fob. The idea has become vague enough, though, that mention of a firearm with any type of RFID technology embedded would probably raise the specter of the smart gun to gun-rights advocates.

Further, devices embedded in firearms that count the number of rounds fired have been proposed for decades, if not a century, as a means of accountability. The holder of a weapon could, in theory, be required to positively account for every round fired. That could eliminate incidents of unreported use of force by police, for example. In practice I think this is less compelling than it sounds, simple counting of rounds leaves too many opportunities to fudge the numbers and conceal real-world use of a weapon as range training, for example.

That said, the NRA has long been vehemently opposed to the incorporation of any sort of technology into weapons that could potentially be used as a means of state control or regulation. The concern isn't completely unfounded; the state of New Jersey did, for a time, have legislation that would have made user-identifying "smart guns" mandatory if they were commercially available. The result of the NRA's strident lobbying is that no such gun has ever become commercially available; "smart guns" have been such a political third rail that any firearms manufacturer that dared to introduce one would probably face a boycott by most gun stores. For better or worse, a result of the NRA's powerful political advocacy in this area is that the concept of embedding security or accountability technology into weapons has never been seriously pursued in the US. Even a tentative step in that direction can produce a huge volume of critical press for everyone involved.

I bring this up because I think it explains some of why VAI seems a bit vague and cagey about the round-counting capabilities of their tags. They position it as purely a maintenance feature, allowing the armorer to keep accurate tabs on the preventative maintenance schedule for each individual weapon (in armory environments, firearm users are often expected to report how many rounds they fired for maintenance tracking reasons). The resistance of RuBee tags to concealment is only positioned as a deterrent to theft, although the idea of RuBee-tagged firearms creates obvious potential for security screening. Probably the most profitable option for VAI would be to promote RuBee-tagged firearms as tool for enforcement of gun control laws, but this is a political impossibility and bringing it up at all could cause significant reputational harm, especially with the government as a key customer. The result is marketing copy that is a bit odd, giving a set of capabilities that imply an application that is never mentioned.

VAI found an incredible niche with their arms-tracking application. Institutional users of firearms, like the military, police, and security forces, are relatively price-insensitive and may have strict accounting requirements. By the mid-'00s, VAI was into the long sales cycle of proposing the technology to the military. That wasn't entirely unsuccessful. RuBee shot-counting weapon inventory tags were selected by the Naval Surface Warfare Center in 2010 for installation on SCAR and M4 rifles. That contract had a five-year term, it's unclear to me if it was renewed. Military contracting opened quite a few doors to VAI, though, and created a commercial opportunity that they eagerly pursued.

Perhaps most importantly, weapons applications required an impressive round of safety and compatibility testing. RuBee tags have the fairly unique distinction of military approval for direct attachment to ordnance, something called "zero separation distance" as the tags do not require a minimum separation from high explosives. Central to that certification are findings of intrinsic safety of the tags (that they do not contain enough energy to trigger explosives) and that the magnetic fields involved cannot convey enough energy to heat anything to dangerous temperatures.

That's not the only special certification that RuBee would acquire. The military has a lot of firearms, but military procurement is infamously slow and mercurial. Improved weapon accountability is, almost notoriously, not a priority for the US military which has often had stolen weapons go undetected until their later use in crime. The Navy's interest in RuBee does not seem to have translated to more widespread military applications.

Then you have police departments, probably the largest institutional owners of firearms and a very lucrative market for technology vendors. But here we run into the political hazard: the firearms lobby is very influential on police departments, as are police unions which generally oppose technical accountability measures. Besides, most police departments are fairly cash-poor and are not likely to make a major investment in a firearms inventory system.

That leaves us with institutional security forces. And there is one category of security force that are particularly well-funded, well-equipped, and beholden to highly R&D-driven, almost pedantic standards of performance: the protection forces of atomic energy facilities.

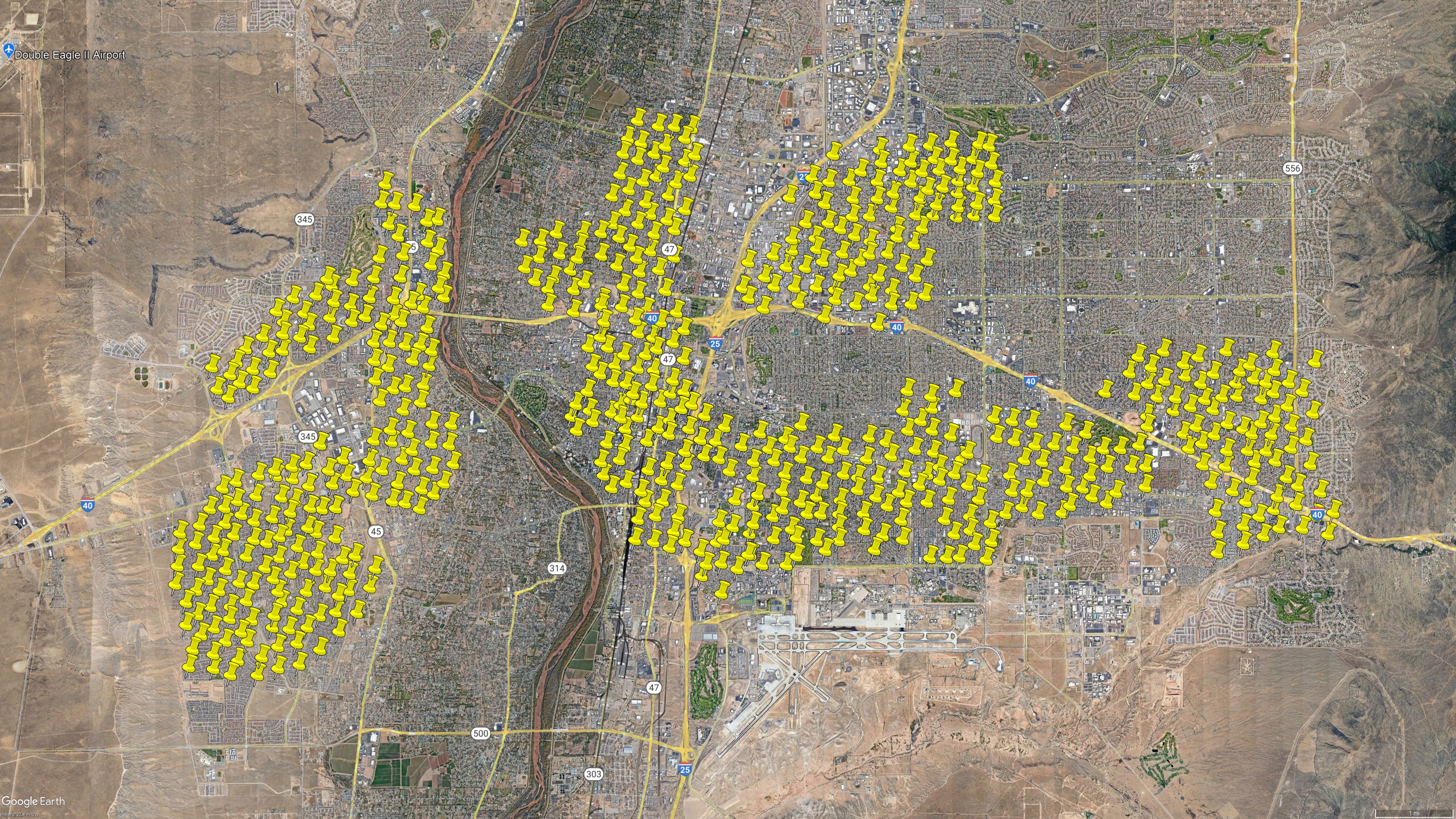

Protection forces at privately-operated atomic energy facilities, such as civilian nuclear power plants, are subject to licensing and scrutiny by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Things step up further at the many facilities operated by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Protection forces for NNSA facilities are trained at the Department of Energy's National Training Center, at the former Manzano Base here in Albuquerque. Concern over adequate physical protection of NNSA facilities has lead Sandia National Laboratories to become one of the premier centers for R&D in physical security. Teams of scientists and engineers have applied sometimes comical scientific rigor to "guns, gates, and guards," the traditional articulation of physical security in the nuclear world.

That scope includes the evaluation of new technology for the management of protection forces, which is why Oak Ridge National Laboratory launched an evaluation program for the RuBee tagging of firearms in their armory. The white paper on this evaluation is curiously undated, but citations "retrieved 2008" lead me to assume that the evaluation happened right around the middle of the '00s. At the time, VAI seems to have been involved in some ultimately unsuccessful partnership with Oracle, leading to the branding of the RuBee system as Oracle Dot-Tag Server. The term "Dot-Tag" never occurs outside of very limited materials around the Oracle partnership, so I'm not sure if it was Oracle branding for RuBee or just some passing lark. In any case, Oracle's involvement seems to have mainly just been the use of the Oracle database for tracking inventory data---which was naturally replaced by PostgreSQL at Oak Ridge.

The Oak Ridge trial apparently went well enough, and around the same time, the Pantex Plant in Texas launched an evaluation of RuBee for tracking classified tools. Classified tools are a tricky category, as they're often metallic and often stored in metallic cases. During the trial period, Pantex tagged a set of sample classified tools with RuBee tags and then transported them around the property, testing the ability of the RuBee controllers to reliably detect them entering and exiting areas of buildings. Simultaneously, Pantex evaluated the use of RuBee tags to track containers of "chemical products" through the manufacturing lifecycle. Both seem to have produced positive results.

There are quite a few interesting and strange aspects of the RuBee system, a result of its purpose-built Visibility Network nature. A RuBee controller can have multiple antennas that it cycles through. RuBee tags remain in a deep-sleep mode for power savings until they detect a RuBee carrier during their periodic wake cycle. When a carrier is detected, they fully wake and listen for traffic. A RuBee controller can send an interrogate message and any number of tags can respond, with an interesting and novel collision detection algorithm used to ensure reliable reading of a large number of tags.

The actual RuBee protocol is quite simple, and can also be referred to as IEEE 1902.1 since the decision of VAI to put it through the standards process. Packets are small and contain basic addressing info, but they can also contain arbitrary payload in both directions, perfect for data loggers or sensors. RuBee tags are identified by something that VAI oddly refers to as an "IP address," causing some confusion over whether or not VAI uses IP over 1902.1. They don't, I am confident saying after reading a whole lot of documents. RuBee tags, as standard, have three different 4-byte addresses. VAI refers to these as "IP, subnet, and MAC," 2 but these names are more like analogies. Really, the "IP address" and "subnet" are both configurable arbitrary addresses, with the former intended for unicast traffic and the latter for broadcast. For example, you would likely give each asset a unique IP address, and use subnet addresses for categories or item types. The subnet address allows a controller to interrogate for every item within that category at once. The MAC address is a fixed, non-configurable address derived from the tag's serial number. They're all written in the formats we associate with IP networks, dotted-quad notation, as a matter of convenience.

And that's about it as far as the protocol specification, besides of course the physical details which are a 131,072 Hz carrier, 1024 Hz data clock, either ASK or BPSK modulation. The specification also describes an interesting mode called "clip," in which a set of multiple controllers interrogate in exact synchronization and all tags then reply in exact synchronization. Somewhat counter-intuitively, because of the ability of RuBee controllers to separate out multiple simultaneous tag transmissions using an anti-collision algorithm based on random phase shifts by each tag, this is ideal. It allows a room, say an armory, full of RuBee controllers to rapidly interrogate the entire contents of the room. I think this feature may have been added after the Oak Ridge trials...

RuBee is quite slow, typically 1,200 baud, so inventorying a large number of assets can take a while (Oak Ridge found that their system could only collect data on 2-7 tags per second per controller). But it's so robust that it an achieve a 100% read rate in some very challenging scenarios. Evaluation by the DoE and the military produced impressive results. You can read, for example, of a military experiment in which a RuBee antenna embedded in a roadway reliably identified rifles secured in steel containers in passing Humvees.

Paradoxically, then, one of the benefits of RuBee in the military/defense context is that it is also difficult to receive. Here is RuBee's most interesting trick: somewhat oversimplified, the strength of an electrical radio signal goes as 1/r, while the strength of a magnetic field goes as 1/r^3. RuBee equipment is optimized, by antenna design, to produce a minimal electrical field. The result is that RuBee tags can very reliably be contacted at short range (say, around ten feet), but are virtually impossible to contact or even detect at ranges over a few hundred feet. To the security-conscious buyer, this is a huge feature. RuBee tags are highly resistant to communications or electronic intelligence collection.

Consider the logical implications of tagging the military's rifles. With conventional RFID, range is limited by the size and sensitivity of the antenna. Particularly when tags are incidentally powered by a nearby reader, an adversary with good equipment can detect RFID tags at very long range. VAI heavily references a 2010 DEFCON presentation, for example, that demonstrated detection of RFID tags at a range of 80 miles. One imagines that opportunistic detection by satellite is feasible for a state intelligence agency. That means that your rifle asset tracking is also revealing the movements of soldiers in the field, or at least providing a way to detect their approach.

Most RuBee tags have their transmit power reduced by configuration, so even the maximum 100' range of the protocol is not achievable. VAI suggests that typical RuBee tags cannot be detected by radio direction finding equipment at ranges beyond 20', and that this range can be made shorter by further reducing transmit power.

Once again, we have caught the attention of the Department of Energy. Because of the short range of RuBee tags, they have generally been approved as not representing a COMSEC or TEMPEST hazard to secure facilities. And that brings us back to the very beginning: why does the DoE use a specialized, technically interesting, and largely unique radio protocol to fulfill such a basic function as nagging people that have their phones? Because RuBee's security properties have allowed it to be approved for use adjacent to and inside of secure facilities. A RuBee tag, it is thought, cannot be turned into a listening device because the intrinsic range limitation of magnetic coupling will make it impossible to communicate with the tag from outside of the building. It's a lot like how infrared microphones still see some use in secure facilities, but so much more interesting!

VAI has built several different product lines around RuBee, with names like Armory 20/20 and Shot Counting Allegro 20/20 and Store 20/20. The founder started his career in eye health, remember. None of them are that interesting, though. They're all pretty basic CRUD applications built around polling multiple RuBee controllers for tags in their presence.

And then there's the "Alert 20/20 DoorGuard:" a metal pedestal with a RuBee controller and audio announcement module, perfect for detecting government cell phones.

I put a lot of time into writing this, and I hope that you enjoy reading it. If you can spare a few dollars, consider supporting me on ko-fi. You'll receive an occasional extra, subscribers-only post, and defray the costs of providing artisanal, hand-built world wide web directly from Albuquerque, New Mexico.

One of the strangest things about RuBee is that it's hard to tell if it's still a going concern. VAI's website has a press release section, where nothing has been posted since 2019. The whole website feels like it was last revised even longer ago. When RuBee was newer, back in the '00s, a lot of industry journals covered it with headlines like "the new RFID." I think VAI was optimistic that RuBee could displace all kinds of asset tracking applications, but despite some special certifications in other fields (e.g. approval to use RuBee controllers and tags around pacemakers in surgical suites), I don't think RuBee has found much success outside of military applications.

RuBee's resistance to shielding is impressive, but RFID read rates have improved considerably with new DSP techniques, antenna array designs, and the generally reduced cost of modern RFID equipment. RuBee's unique advantages, its security properties and resistance to even intentional exfiltration, are interesting but not worth much money to buyers other than the military.

So that's the fate of RuBee and VAI: defense contracting. As far as I can tell, RuBee and VAI are about as vital as they have ever been, but RuBee is now installed as just one part of general defense contracts around weapons systems, armory management, and process safety and security. IEEE standardization has opened the door to use of RuBee by federal contractors under license, and indeed, Lockheed Martin is repeatedly named as a licensee, as are firearms manufacturers with military contracts like Sig Sauer.

Besides, RuBee continues to grow closer to the DoE. In 2021, VAI appointed Lisa Gordon-Hagerty to it board of directors. Gordon-Hagerty was undersecretary of Energy and had lead the NNSA until the year before. This year, the New Hampshire Small Business Development Center wrote a glowing profile of VAI. They described it as a 25-employee company with a goal of hitting $30 million in annual revenue in the next two years.

Despite the outdated website, VAI claims over 1,200 RuBee sites in service. I wonder how many of those are Alert 20/20 DoorGuards? Still, I do believe there are military weapons inventory systems currently in use. RuBee probably has a bright future, as a niche technology for a niche industry. If nothing else, they have legacy installations and intellectual property to lean on. A spreadsheet of VAI-owned patents on RuBee, with nearly 200 rows, encourages would-be magnetically coupled visibility network inventors not to go it on their own. I just wish I could get my hands on a controller....

-

I have found some conflicting information on the date, it could have been as early as 2002. 2004 is the year I have the most confidence in.↩

-

The documentation is confusing enough about these details that I am actually unclear on whether the RuBee "MAC address" is 4 bytes or 6. Examples show 6 byte addresses, but the actual 1902.1 specification only seems to allow 4 byte addresses in headers. Honestly all of the RuBee documentation is a mess like this. I suspect that part of the problem is that VAI has actually changed parts of the protocol and not all of their products are IEEE 1902.1 compliant.↩